![]()

By Chabella Guzman, PREEC communications

Water can be a life-giving source and a destructive one. With aging water infrastructure in the Panhandle of Nebraska, communities are becoming more aware of the latter.

Agriculture is an economic driver in the Panhandle, but the land receives comparatively little rainfall. So, early settlers of the area created a system of dams and irrigation canals. A century later, this infrastructure is aging and, in some circumstances, in need of repair.

A recent Nebraska Natural Resources District assessment of 2,969 dams in Nebraska found that about 148 dams could be classified as having high hazard potential, meaning failure or a malfunction would likely have significant economic impacts or even endanger people.

“Many of our (Panhandle) dams are earth-fill dams, constructed in small reservoirs and at the time didn’t need concrete dams,” said Mohamed Khalil, Nebraska Extension assistant geoscientist of applied geophysics. The structure of an earthen dam can be compromised in many ways, from trees to animals. Khalil said the biggest problem can be a permeable layer inside or under the dam, creating a seepage zone.

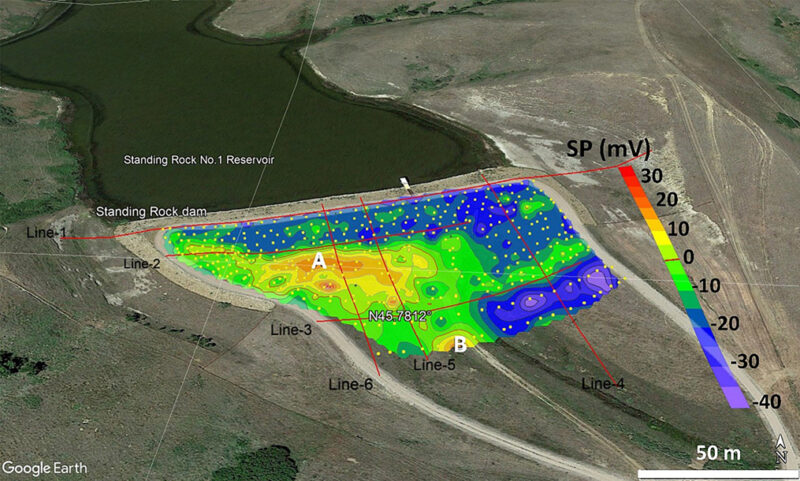

In 2023, Khalil studied the seepage through the Standing Rock Dam No.1 in South Dakota. Seepage of the dam was detected by using geophysical methods, such as electrical resistivity tomography (ERT) and self-potential (SP), which provide a convenient, cost-effective, rapid, nondestructive, and repeatable means to outline the location and define the magnitude of water seepage through hydraulic structures.

The sensors were removed after the study, but Khalil said they could create a sensor relay and monitor a dam or canal 24/7 if requested.

“The sensors can also be used with other types of infrastructures,” he said. “I completed a project with a sanitary district in South Dakota and discovered a large seepage zone that dissolved subsurface gypsum over time and created many types of sinkholes in the area.” Khalil said the sensors could also detect leaks at animal waste storage ponds and treatment lagoons.

While infrastructure concerns are valid, Nebraska Extension can help. To learn more on ways to prevent and check for seepage, leaks, or even sinkholes resulting from subsurface erosion, contact Mohamed Khalil, Nebraska Extension assistant geoscientist of applied geophysics, by email at maboushanab2@unl.edu or call 308-633-0980.