![]()

By TYLER ELLYSON

UNK Communications

As the weather warms, more Nebraskans head outdoors to enjoy activities such as fishing, hiking and camping.

But they’re not alone. There’s another creature that’s most active during the spring and summer months.

Nebraska is home to a growing number of tick species. When these arachnids cross paths with humans, the consequences can be dire.

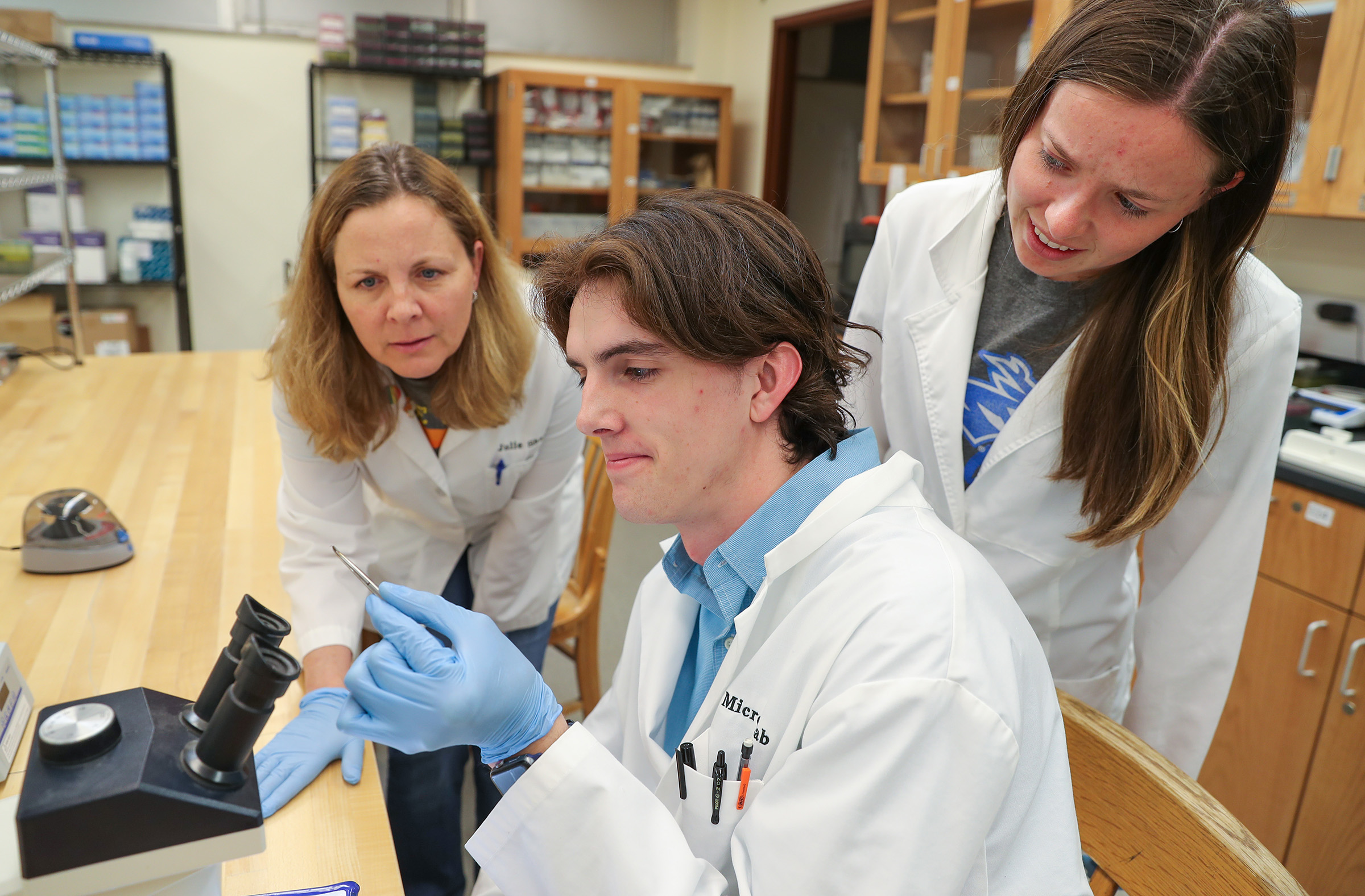

(Photo by Erika Pritchard, UNK Communications)

“Tickborne disease is on the rise in the United States. In fact, we have more tickborne vectored disease than mosquito-borne vectored disease. We tend to think about mosquitoes, but ticks are actually the bigger problem,” said Julie Shaffer, a biology professor and department co-chair at the University of Nebraska at Kearney.

Nearly half a million Americans are diagnosed with a tickborne illness each year, according to Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimates, with Lyme disease representing the vast majority of reported cases. Ehrlichiosis, tularemia and Rocky Mountain spotted fever are also transmitted through tick bites.

Experts believe both human and tick movements are contributing to the increase in these diseases. More people are building homes in formerly uninhabited wilderness areas, and climate change is allowing some tick species to move into new areas. While the American dog tick remains the most common species in Nebraska, the lone star tick is also spreading in the state and the black-legged tick (deer tick) now has established populations here. Another new species, the Gulf Coast tick, was discovered in Lancaster County in 2018.

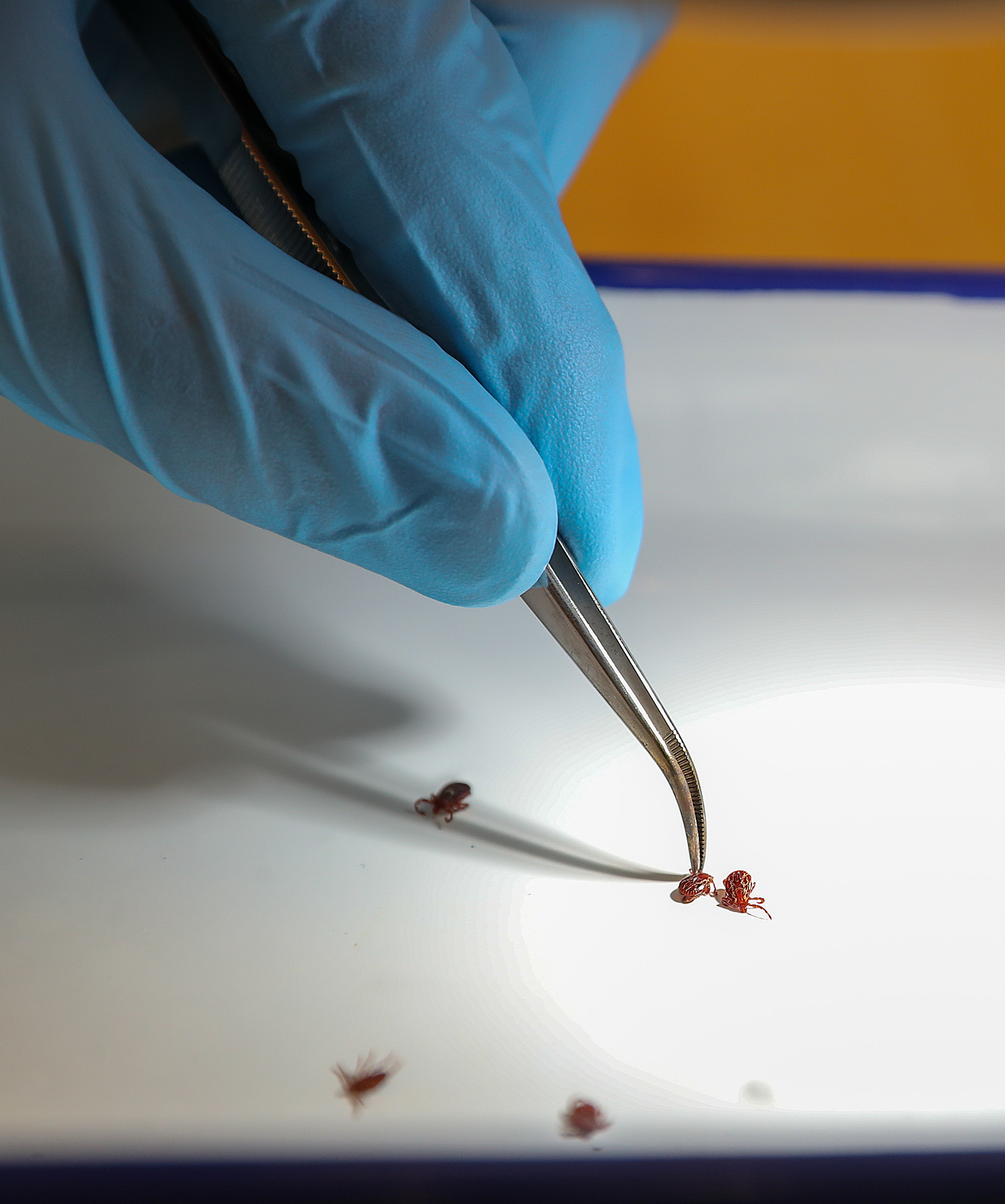

(Photo by Erika Pritchard, UNK Communications)

Each species presents a different risk to people and animals. That’s why scientists like Shaffer are working with public health officials to better understand these pesky parasites and the diseases they spread.

“We need to know more about disease prevalence rates in our state, which ticks are carrying these diseases, how that transmission occurs and what the risk is for people in a certain area,” said Shaffer, who’s been studying tickborne pathogens for several years.

The UNK professor and her research assistants – currently three undergraduate students and one graduate student – collect thousands of ticks every spring and summer at locations throughout the state. Their process is quite simple: drag a large piece of felt across a grassy area and let the ticks latch on.

(Photo by Erika Pritchard, UNK Communications)

The ticks are then disinfected in alcohol, sorted by sex and species, and frozen until it’s time to extract their DNA for testing. They use a technique called polymerase chain reaction (PCR) to determine whether a tick is carrying a specific pathogen.

By identifying which ticks and diseases are present in specific locations, the researchers can help medical professionals make a timely diagnosis when someone is infected.

“Most of these bacterial infections from ticks have similar symptoms, and some of them are more virulent than others, so you have to get treatment more quickly,” Shaffer said. “If you don’t know what to expect, you may not get that person the right treatment fast enough.”

(Photo by Erika Pritchard, UNK Communications)

Rocky Mountain spotted fever and tularemia can be fatal if they’re not treated properly, and Lyme disease has the potential to be debilitating.

“This type of surveying work is important because tickborne illnesses can present with vary vague symptoms and they can be very hard to diagnose,” said UNK junior Nicole Messbarger, a pre-medical student from Kearney. “We want to inform health care providers and the general public about the risks of an area so people receive the early treatment that can make such a big difference in these cases.”

Messbarger joined Shaffer’s research team last May as a member of the Undergraduate Research Fellows program and she’s already noticed a couple alarming trends. They’re finding more lone star ticks in central Nebraska and a higher prevalence of the bacteria that cause tularemia and Rocky Mountain spotted fever.

(Photo by Erika Pritchard, UNK Communications)

“We expected to find mainly dog ticks in this area, because that’s what’s known to be here, but the lone star tick is also moving northward,” said Messbarger, who presented her findings during the annual Research Day competition on campus.

In addition to what they collect, the UNK researchers test ticks sent to them by the Nebraska Department of Health and Human Services, typically from areas where there’s been suspected disease transmission. Working with collaborators at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln, Creighton University and University of Nebraska Medical Center, they hope to secure federal funding to develop a device that can quickly perform this testing in the field, rather than a lab setting.

In the meantime, they’ll expand their research by studying young nymphs and their ability to transmit diseases, focusing on whether different tick species can exchange infectious bacteria with each other and using an advanced PCR test to determine how many bacteria are needed to make a person sick.